It is no question that modern diagnostic imaging and radiation therapy machines play large parts in today’s healthcare. But where did x-ray usage begin? Let’s journey through the timeline of when the first x-ray was taken to today and the growth of its technology into some of the most common machines you may see for diagnostic imaging and radiation therapy.

Diagnostic Imaging

1895

Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen, a physicist, became the first person to observe x-rays, and quite accidentally. Röntgen noticed a glow coming from a nearby chemically coated screen while testing whether cathode rays (known today as electron beams) could pass through glass. After examining the rays emanating from the electrons impacting the glass and their unknown nature, Röntgen dubbed them as “X-rays”. He learned that x-rays could penetrate human flesh but less so higher density substances like bone or lead, and that they were photographable.1

Röntgen’s work paved the way for x-rays to become a vital diagnostic tool in medicine. Dentists such as Otto Walkhoff, Frank Harrison, and Walter König helped spark the advancement of dental radiography, publishing their findings on the topic in 1896.2 During the Balkan War in 1897, doctors used the rapidly improving x-ray radiographs to find bullets and broken bones inside patients on the battlefield.1

1900-1950

Fluoroscopy was invented after the discovery of x-rays in 1900. Continuing into the 20th century, x-rays and fluoroscopy became popular on a consumer level without the risk fully understood. There were rising reports of burns or other skin damage after x-ray radiation exposure; Thomas Edison’s assistant, Clarence Dally, even passed away from skin cancer in 1904 after working extensively with x-rays. Regardless, products like shoe-fitting fluoroscopes were popular from the 1930s until the 1950s so customers at shoe stores could see the bones in their feet.1

On a medical level, scientists progressed with inventing the modern x-ray tube, introducing film into radiology, and the first mammography. Reseachers performed further studies to get a better understanding of the genetic effects of x-ray exposure and the damage caused. Using fluoroscopes in shops tapered off starting in the 1950’s, the practice proven more dangerous than beneficial.3

1970s

X-rays began transitioning into digital imaging by the 1970s which helped save time, money, and storage space.4 Godfrey Hounsfield of EMI Laboratories created the first commercially available CT scanner in 1972. He co-invented the technology with physicist Dr. Allan Cormack and both researchers were later on jointly awarded the 1979 Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine.

The cross-sectional imaging, or “slices”, from CT scans made diagnosing health issues like heart disease, tumors, internal bleeding, and fractures simpler for doctors while also being easier on the patients. Through the following years, with how effective the CT scanners proved to be improvements on the design were quickly developed.5

1990s

In the early 1990s, developments with x-ray computed tomography came into a new realm of imaging. Newer CT scanners allowed for the X-ray source to scan in a continuous spiral around the body, which gave an image of a whole organ at once instead of individual cross sections.5 This technique is called helical or spiral CT scanning. C-arm machines created by companies such as Philips introduced Rotational Angiography, in which the C-arm takes a series of images around the patient. This generates an almost 3D picture when viewing the images in a loop.6

Diagnostic Imaging of Today

Diagnostic imaging from the 2000s to present day demonstrate enhanced versions of all diagnostic tools from history. Doctors still use general x-rays for determining severity of injury, check disease, and to evaluate treatment. CT scans have continued to develop so that analysis of issues occurring in a patient’s body can be more clearly seen to determine treatment.7 Mammograms have become instrumental in determining early diagnosis of breast cancer; fluoroscopy still helps doctors today determine effect of movement to certain areas of the body–although not to determine if you should buy a pair of shoes.

Within dental care, veterinary work, and even unexpected industries such as manufacturing and mining, diagnostic imaging has proven its worth.

Radiation Therapy

1895 – 1910

The discovery of x-rays also ushered in research on radiation treatment, eventually leading to some of the machines we see in today’s healthcare. Use of x-ray treatments began between 1895 and 1900, generally delivered as singular, large exposures to the necessary areas. Despite the high doses, the treatments proved to be insufficient over the area of exposure for actual treatment of malignancies, appearing to cause extensive damage to normal surrounding tissues instead.8

1911

As damage from radiation to healthy tissues became more widely known as an issue within the medical world, solutions to a more controlled type of treatment came to creation in 1911. Around this time external beam radiotherapy (XRT) and slow, continuous low-dose-rate (LDR) radium treatments were established from the studied principle of fractionation.8 Splitting the total radiation dose into smaller fractions and delivering it over days achieved better management over cancer growth even while reducing adverse effects to non-cancerous areas of the body.

1920 – 1930

The Coolidge tube, initially invented by William D. Coolidge in 1913 as an improvement over the earlier Crookes tube methods to produce x-rays, became the most popular method for x-ray generation during the 1920s. The Crookes tube used a high voltage between an anode and a cathode, depending on the ionization of the gas in the tube for x-ray production. The Coolidge tube introduced a hot cathode that directly produced electrons from its surface allowing for better control of both energy and intensity of the x-rays produced. Coolidge tubes produced x-rays usable for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes.

1930 – 1950

Development of more refined machinery truly began within the 1930s for radiation therapy. One of the first machines used for superficial therapy was the Grenz Ray machine. Dr. Gustav Bucky (inventor of the first x-ray grid as well in 1913), invented and made this machine in the 1930s for commercial use by German company Siemens Reiniger. The Grenz Ray machine was effective as a treatment for skin cancers (superficial cancers) due to the rays not passing deep into the body.9 Bucky labeled the rays Granz, the German word for border, as their biological effects seemed to be bordering those of UV light and traditional x-rays.

Treatments for delving deeper started seeing further progression by 1937 through development of supervoltage x-ray treatment; this dubbed the time period from 1930 – 1950 as the “Orthovoltage Era”. Supervoltage x-ray tubes had a staggeringly high kilovolt range compared to previous machines (50 kV to 200 kV). These orthovoltage treatment machines provided higher and variable energies to treat deeper tumors.8 Continued advancements in the Orthovoltage Era became the beginning of electron beam therapy.

1950 – 1980

From the rise in supervoltage x-ray treatment and through inspiration from other machines such as the Grenz Ray machine emerged the linear accelerator. Also known as a LINAC, these machines nowadays are large devices that emit high energy x-rays and electron beams. After use of the first linear accelerators to treat cancer patients in 1953–with lower energy and restricted range of movement–English physicist Frank Farmer developed a comparison between them and other popular machines of the time. This included resonant transformer units, van de Graaff units, and gamma ray units like Co-60 radiation machines.10

In 1962, the conclusions Farmer came to were that LINACs were the ideal choice for larger departments due to a higher price point and hefty size. However, its design at the time left something to be desired. His hopes for linear accelerator improvements included a more robust operation, smaller unit size, and better vacuum systems. Through manufacturers’ dedicated work on improvements up into the 1970s, the LINAC began to fully establish itself as Farmer’s vision came to life with more stable, reliable, compact, and fully isocentric machines.10

Radiation Therapy of Today

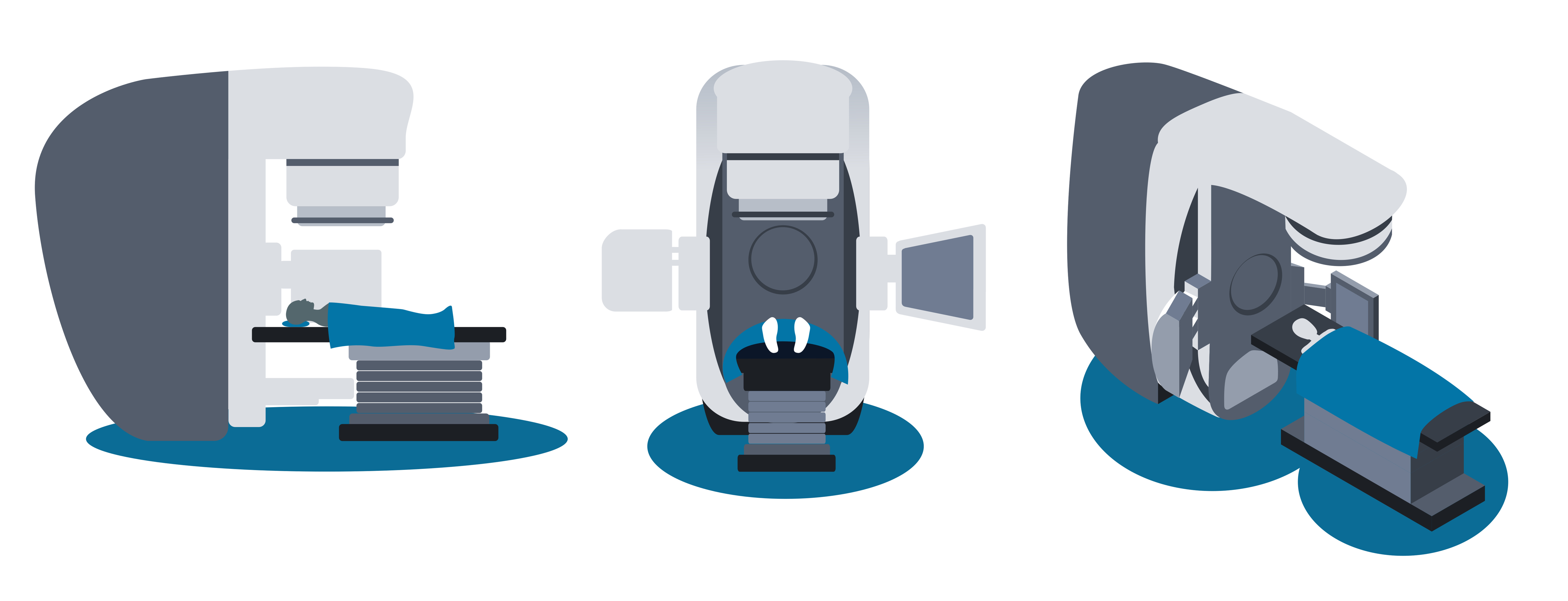

After the 1970s, significant changes to linear accelerators slowed. There were no further radical changes to basic structures and concepts for the generation of the x-ray and electron beams. Modern machines became more sophisticated through other improvements. These were advances in beam shaping through the development of multi-leaf collimators, on-board imaging (OBI), and more recently Flattening Filter Free (FFF) designs to permit much greater dose rates. These system and functionality enhancements keep the linear accelerator as the radiation therapy unit of choice for healthcare today.10 Delivering radiation doses deep into cancerous tumors of a patient while minimizing damage to healthy tissue via intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) is achieved confidently with these ever-improving LINACs.

Through the x-ray technologies developed over the last century, scientists continue to develop new methods to safely deliver radiation therapy. Crossing the linear accelerator with the diagnostic imaging capabilities of CT scanners created TomoTherapy®, another radiotherapy option still widely used today. TomoTherapy® machines allow for more precise tumor targeting and preservation of healthy tissue, taking images of cancerous tumors before treatment. The machine will then rotate during treatment to deliver the radiation dose slice by slice, in a spiral-like pattern.11

X-ray radiotherapy is only one type among many cancer treatments now. However, the machines have been honed through the years to create reliable products for healthcare and even veterinary practices. What was once a general, indirect target of radiation exposure has become an extremely pin-pointed, safer technique for the benefit of patients today.

Summary and Conclusion

In summary, x-rays have come a long way since their discovery in 1895 by Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen, revolutionizing medicine. Used for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes, x-rays underwent significant technological advancements over time starting with producing the first x-ray images on photographic plates. In the early 1900s, the use of x-rays for therapy began with the treatment of skin diseases. By the 1920s, the further developments allowed for the production of higher-energy x-rays. Once in the 1930s, the development of megavoltage x-ray machines allowed for deeper penetration into tissues. Linear accelerators were developed in the 1950s to produce high-energy x-rays and electrons. The 1960s brought the development of computed tomography (CT), which allowed for cross-sectional imaging of the body. In the 1970s, digital radiography was introduced, which allowed for faster image acquisition and processing.

The Versant Physics team has experience that covers a range of equipment including dental units, mobile c-arms and Cone-beam CTs, as well as high energy LINACs and even Proton Therapy units and Cyclotrons. To learn more about how our services can help you, contact us to set up a meeting.

References

- History.com Editors. German scientist discovers X-rays. HISTORY. Published July 17, 2019. https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/german-scientist-discovers-x-rays

- Pauwels, Ruben. (2020). HISTORY OF DENTAL RADIOGRAPHY: EVOLUTION OF 2D AND 3D IMAGING MODALITIES.

- History Of X-Ray Imaging • How Radiology Works. Published March 12, 2021. https://howradiologyworks.com/history-xray-imaging/

- X-Ray Technology: The Past, Present, and Future :: PBMC Health. www.pbmchealth.org. Accessed March 24, 2023. https://www.pbmchealth.org/news-events/blog/x-ray-technology-past-present-and-future#:~:text=Quickly%2C%20military%20doctors%20realized%20the%20life-saving%20potential%20X-rays

- Martino S, Cae R, Reid J, Teresa G, Odle B. Computed Tomography in the 21st Century Changing Practice for Medical Imaging and Radiation Therapy Professionals. Published 2008. https://www.asrt.org/docs/default-source/research/whitepapers/asrt_ct_consensus.pdf?sfvrsn=2ac0c819_8

- How Philips has been advancing patient care with X-ray for more than a century. Philips. https://www.philips.com/a-w/about/news/archive/standard/news/articles/2020/20201106-how-philips-has-been-advancing-patient-care-with-x-ray-for-more-than-a-century.html

- Hanson G. 7 Types of Diagnostic Imaging Tests You May Assist with as a Radiologic Technologist | Rasmussen College. www.rasmussen.edu. https://www.rasmussen.edu/degrees/health-sciences/blog/types-of-diagnostic-imaging/

- Cuffari B. The Evolution of Radiotherapy. News-Medical. Published November 11, 2021. Retrieved on March 24, 2023. https://www.news-medical.net/health/The-Evolution-of-Radiotherapy.aspx.

- Grenz ray machine used for superficial therapy | Science Museum Group Collection. collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk. https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/objects/co134659/grenz-ray-machine-used-for-superficial-therapy-x-ray-machine

- Thwaites DI, Tuohy JB. Back to the future: the history and development of the clinical linear accelerator. Physics in Medicine and Biology. 2006;51(13):R343-R362. doi:https://doi.org/10.1088/0031-9155/51/13/r20

- National Cancer Institute. External Beam Radiation. National Cancer Institute. Published May 1, 2018. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/types/radiation-therapy/external-beam